Electric cells

Electric current is the flow of electric charge. In conductors such as wires and cables, the current consists of moving electrons. Electric cells are chemical devices capable of generating an electric current, producing an electric force that pushes the current along. When a complete circuit of conductors allows the current to flow from one terminal of the cell to the other, a current is established. The current remains constant at any point in the circuit, but if the circuit is broken, the current stops, effectively switching it off. Electrons flow from the negative terminal (cathode) to the positive terminal (anode).

Types of Electric Cells

Electric cells are classified into two types:

- Primary Cells: These cells generate electricity through an irreversible chemical reaction.

- Secondary Cells: These cells can be recharged by passing current through them in reverse.

| Primary Cells | Secondary Cells |

|---|---|

| Contain no fluid, often referred to as dry cells. | Include wet cells (liquid electrolyte) and molten salt cells (liquid with different compositions). |

| Have high internal resistance. | Have lower internal resistance. |

| Have a high energy density. | Have a lower energy density. |

| Undergo irreversible chemical reactions. | Undergo reversible chemical reactions. |

| Require minimal maintenance and can be easily disposed of after use. | Require regular maintenance and are not easily disposed of after use. |

| Have a lower initial cost. | Have a higher initial cost. |

| Cannot be recharged. | Can be recharged multiple times. |

| Convert chemical energy directly into electrical energy when in use. | Convert electrical energy into chemical energy when charging and chemical energy into electrical energy when in use. |

| Smaller and lighter in design. | More complex and heavier in design. |

| Easier to use and operate. | More complex to use compared to primary cells. |

| Have a lower self-discharge rate. | Have a higher self-discharge rate. |

| Commonly used in flashlights and other portable devices for instant power supply. | Used in inverters, automobiles, and other applications requiring rechargeable power. |

Components of an Electric Cell

There are three main components in a cell:

- Electrodes: In a primary cell, these are typically made of different metals, with graphite commonly used.

- Electrolyte: A substance that allows the movement of ions, facilitating the chemical reaction.

- Container: Holds the electrolyte and electrodes.

The Simple Primary Cell (Voltaic Cell)

A simple cell is created by placing two different metal electrodes in an electrolyte. Wires are then connected to these metals and attached to a voltmeter, which measures the potential difference in the circuit. If a deflection is observed on the voltmeter, the cell generates voltage. A rightward deflection indicates that the electrode connected to the positive terminal of the voltmeter is the anode (positive electrode), while the one connected to the negative terminal is the cathode (negative electrode). If the deflection is to the left, the connections should be reversed.

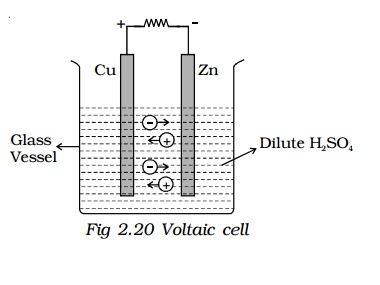

The simple cell or voltaic cell consists of two electrodes, one of copper and the other of zinc dipped in a solution of dilute sulphuric acid in a glass vessel. The copper electrode is the positive pole or copper rod of the cell and zinc is the negative pole or zinc rod of the cell. The electrolyte is dilute sulphuric acid.

Credit: BrainKart

Credit: BrainKart

Defects of a Simple Cell

1. Polarization

Polarization occurs when hydrogen bubbles form on the positive electrode, insulating it and reducing the efficiency of the cell. This defect slows down and eventually stops the operation of the cell. It can be corrected by:

- Occasionally brushing the plates (though this is inconvenient).

- Using a depolarizer, such as manganese dioxide, which oxidizes hydrogen and removes the bubbles.

2. Local Action

Local action occurs when impure zinc is used, leading to gradual corrosion of the zinc plates. This can be prevented by:

- Cleaning the zinc with sulfuric acid (H2SO4).

- Rubbing the zinc with mercury, which forms an amalgam that covers impurities and prevents unwanted reactions with the electrolyte.

Leclanché Cell

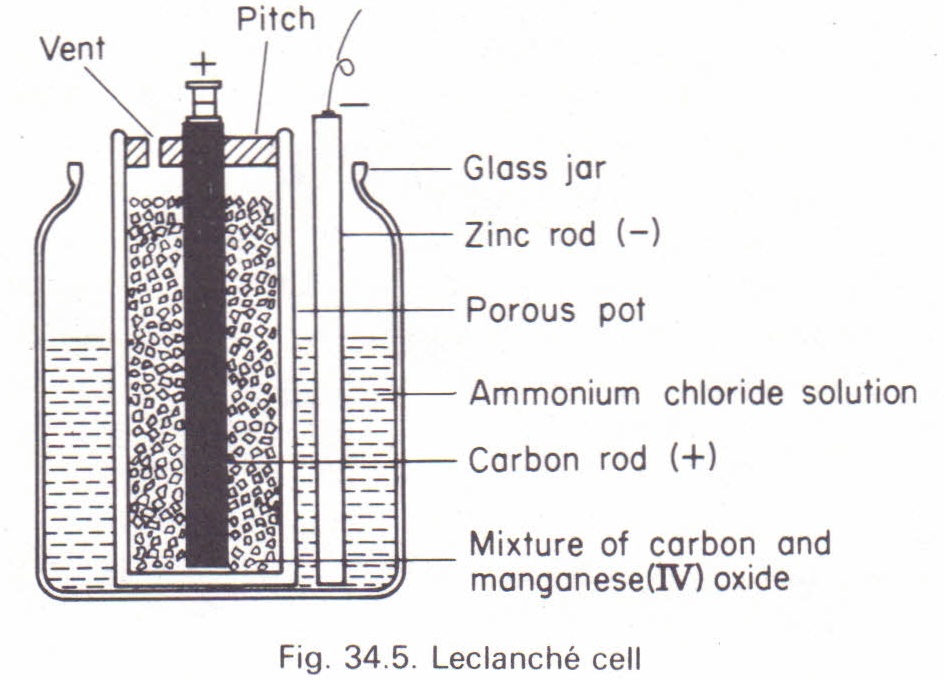

Leclanché cells are classified into two types: wet and dry. The wet Leclanché cell consists of a zinc rod acting as the cathode, immersed in an ammonium chloride solution within a glass container. The anode is a carbon rod enclosed in a porous pot, surrounded by manganese dioxide, which serves as a depolarizer.

An electromotive force (e.m.f) is generated by the interaction between zinc, carbon, and the electrolyte, causing current to flow from the zinc electrode to the carbon electrode within the cell. Externally, the current moves from carbon to zinc.

The e.m.f of a Leclanché cell is approximately 1.5 volts. However, one major drawback is polarization, which occurs when hydrogen bubbles accumulate on the carbon electrode, reducing efficiency. This issue can be mitigated by allowing the cell to rest periodically. Additionally, the wet Leclanché cell is unsuitable for portable use due to the risk of spillage.

Credit: PhysicsMax

Credit: PhysicsMax

Dry Leclanché Cell

To overcome portability issues, the dry Leclanché cell was developed. Here, the ammonium chloride electrolyte is in a jelly-like paste rather than a liquid solution. The carbon rod, acting as the positive electrode, is surrounded by a mix of manganese dioxide and powdered carbon inside a zinc container, which serves as the negative electrode.

Dry cells are lightweight and easy to transport, making them ideal for use in devices such as flashlights and transistor radios. However, they deteriorate over time due to local action.

Daniel Cell

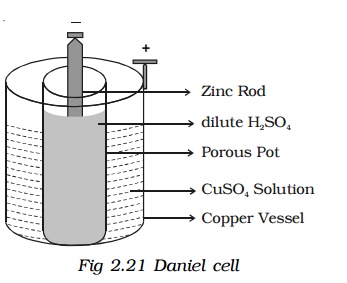

The Daniel cell was invented to address the issue of polarization. It consists of a zinc rod as the negative electrode and a copper container as the positive electrode. The electrolyte is a dilute sulfuric acid solution contained within a porous pot around the zinc rod, while the depolarizer is copper sulfate solution in the surrounding copper container.

The Daniel cell provides a more stable e.m.f of approximately 1.08 volts, making it more reliable than the Leclanché cell.

Credit: BrainKart

Credit: BrainKart

Secondary Cells

Secondary cells can be recharged after use. The two main types are:

- Lead-acid accumulator

- Alkaline (NiFe) accumulator

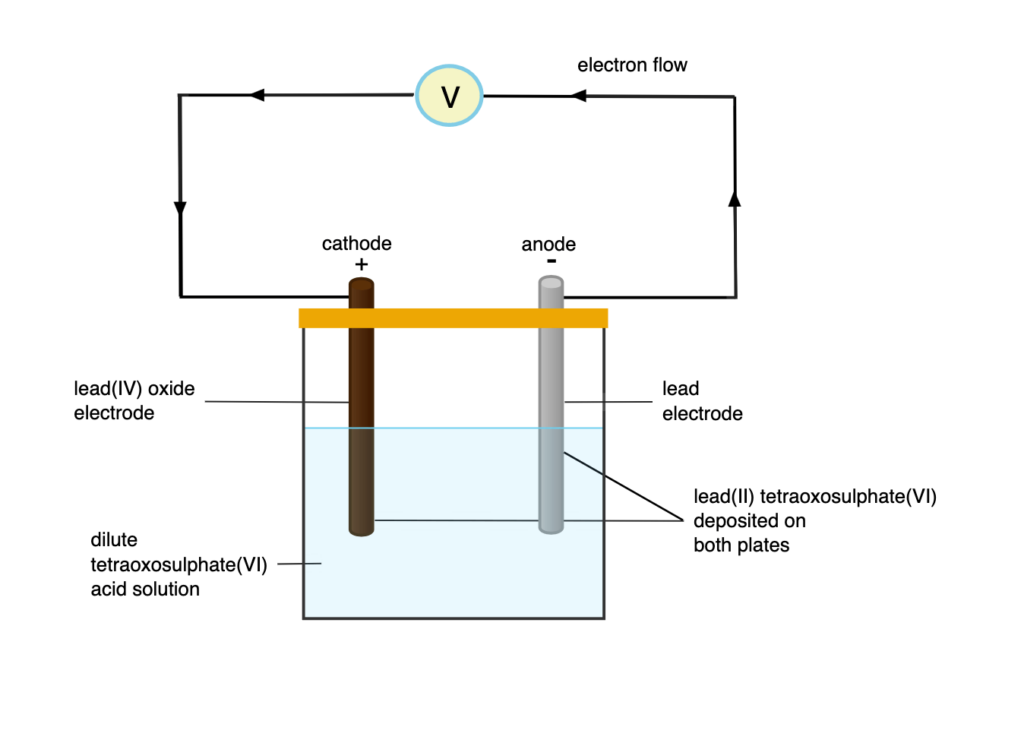

Lead-Acid Accumulator

This is the most common type of secondary cell. It consists of lead oxide as the positive electrode, lead as the negative electrode, and sulfuric acid as the electrolyte. During discharge, the plates gradually convert to lead sulfate, and the acid becomes diluted. A fully charged cell has an e.m.f of 2.2V and a relative density of 1.25. When discharged, the values drop below 2.0V and 1.15, respectively.

Credit: Kofastudy

Credit: Kofastudy

Maintenance of Lead-Acid Accumulators

- Maintain electrolyte levels with distilled water.

- Recharge the cell when the acid density falls below 1.15; it is fully charged at 1.25.

- If unused for long periods, discharge occasionally or remove the acid and store the cell dry.

- Keep the battery clean to prevent current leakage.

Alkaline (NiFe) Accumulator

The NiFe accumulator is named after its primary elements: nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe). The positive electrode is made of nickel hydroxide, while the negative electrode is composed of iron or cadmium. The electrolyte is potassium hydroxide dissolved in water.

These cells last longer, retain charge better than lead-acid accumulators, and require minimal maintenance. They are commonly used in factories and hospitals for emergency power supplies. However, they are bulkier, more expensive, and have a lower e.m.f of approximately 1.25V.

Comparison of Different Cells

| Cell Type | Positive Terminal | Negative Terminal | Electrolyte | Depolarizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Cell | Copper Plate | Zinc Rod | Dilute Sulfuric Acid | None |

| Daniel Cell | Copper Container | Zinc Rod | Dilute Sulfuric Acid | Copper Sulfate Solution |

| Leclanché (Wet) | Carbon Rod | Zinc Rod | Ammonium Chloride Solution | Manganese Dioxide |

| Leclanché (Dry) | Carbon Rod | Zinc Container | Ammonium Chloride Paste | Manganese Dioxide |

| Lead-Acid Accumulator | Lead Oxide | Lead | Dilute Sulfuric Acid | None |